Are the Philistines on the march over at the

Guardian? Joe Queenan just published there a

splenetic outburst against modern art. He doesn't seem to like much after about 1900. Terry Teachout does

his own examination of Queenan's hostility at the

Wall Street Journal. Complaints about modern art -- I don't mean just negative reactions to anything new, but sustained, visceral dislike for the modern -- are as old as modern art itself.

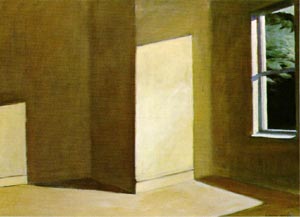

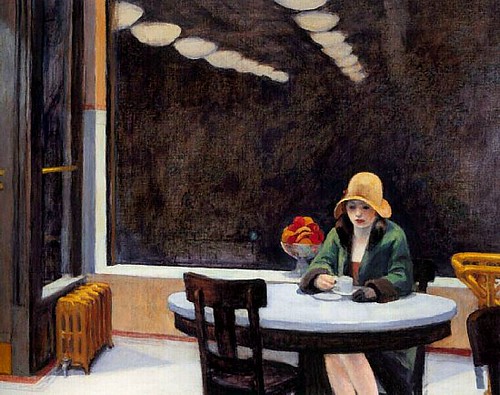

There is a problem with artistic modernism, especially music. But the problem is more recent than Queenan thinks and dates from the 1950s, not the 1900s. It is true that the "break" that defines modernism happened some time in the decade or so before 1914, and much of modern art's problem with the general public dates from those years. But the literature and visual art of that period have long since been been assimilated by both critics and the general public, and the same is true of most of its music. The later art of the 20th century has just been a working out of that moment: the breakdown of inherited realist, classical, and romantic esthetics.

Since 1945, the fates of the arts have diverged. Literature has proven the most conservative, largely abandoning the modernistic experiments of, say, Proust, Joyce, and Nabakov. There is widespread admiration for their achievements, but few serious imitators. Literature's close relation to time-bound narrative, reinforced by the ubiquity of movies and television, made that fate difficult to avoid. The visual arts suffered a different fate: widespread appreciation of and big money for signature breakthrough works. Still, there were fewer and fewer serious imitators and practitioners in the last century's concluding decades.

Something entirely different happened to music. While undergoing wrenching changes from the end of the nineteenth century -- the rise of commercialized popular music, the influence of non-Western musical cultures, the exhaustion of the classical-romantic paradigm -- Western "art" music was still vigorous down to the Second World War. The distinction between "popular" and "high" music had not yet become a chasm. Contrary to Queenan and other critics,* the twentieth-century repertory is second only to the nineteenth century's in being studied, played, and listened to.**

The true failure of modern art happened after 1945. The sheer destructiveness of the Second World War had multiple, devastating impacts on European centers of art, reinforcing the existing disruptions of war, revolution, and exile. Classical music, especially the core Romantic and Austro-German traditions, has taken its time recovering from the way it was misused by the collectivist movements and totalitarian states of the first half of the twentieth century. The straddling of popular and classical musical cultures, by the 1950s, seemed fatally compromised by either accusations of "selling out" or knuckling under to the agit-prop demands of "socialist realism." On the other hand, the unprecedented explosion of techniques and resources for popular music, starting in the late 50s, pulled audiences elsewhere. Then television miniaturized everyone's mind.

And something else went wrong in the decades after 1945: the academicization of once-radical artistic tendencies, especially Expressionism, a movement that started in Germanic countries as a reaction to the popular cheapening of Romanticism. Expressionism was a brief but potent episode of "hyper-romanticism," in the sense of validating the artist's expression of (usually negative) inner feelings, regardless of external form or audience comprehension. It's impossible to systematize such a tendency. The originating works of this movement have still not lost, and probably will never lose, their power to shock. Yet, starting in the 1920s with Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, attempts have been made to reduce it to formula. Formulas enabled lesser talents to create lifeless imitations of something that can't be mimicked. Appreciation and artistic creation became mired in a familiar Germanic-academic tendency to load esthetic values down with a lot of heavy theorizing.† After 1945, the spread of higher education put this questionable and half-digested theorizing on everyone's dinner table, as it were.††

Esthetics begins and ends with the senses, not Theory.‡ The origins of modern Western art lie in the happy symbiosis of the inward feeling of the northern peoples (Germans, Celts, Slavs, and others) with classical notions of proportion, form, and timing preserved by the Italians and French. Modernism began to sprout in the late nineteenth century when that symbiosis broke down, and the Germanic and the non-Germanic went their separate ways.

---

* Like Henry Pleasants, whose

Agony of Modern Music (1955) is entertaining, right in many details, and wrong in the big picture.

** I use "nineteenth century" loosely, running from late classical (late Haydn, mature Mozart and Beethoven) through late romantic, bordering on modern (Mahler and Strauss). The "high" modern period ran from the 1890s until the 1950s, from Debussy through, say, Bartók and Bernstein.

† A complaint made earlier and more effectively by Tom Wolfe in his

Painted Word and

From Bauhaus to Our House. The Germans themselves have a nifty term,

Augenmusik -- "music for the eyes" and not for the ears.

†† Perceptive readers will sense the tortured ghost of Allan Bloom and his prolix, controversial

Closing of the American Mind haunting this posting. The trouble with Bloom's book is that he took twice as many words as needed to make his (largely valid) point.

‡ "... this blathering jargon, which so warms the hearts of philosophy professors ..." (Schoenberg himself).

Labels: art, books, journalism, movies, music, Queenan, Teachout, world wars

Panoramic photography was popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before the rise of movies. Photographers would take multiple still photos from different perspectives on a scene, then assemble the photos next to each other to recover the full scene. A panorama could project a scene wider than a person could see at one glance by the naked eye.

Panoramic photography was popular in the 19th and early 20th centuries, before the rise of movies. Photographers would take multiple still photos from different perspectives on a scene, then assemble the photos next to each other to recover the full scene. A panorama could project a scene wider than a person could see at one glance by the naked eye.